-

Carlin Talks History posted in the group U.S. History

The Battle of Sackett’s Harbour

By Patrick A WilderChapter One

Soon after the United States declared war against the United Kingdom on June 18, 1812, spirited American troops began assembling at Greenbush on the Upper Hudson River, directly opposite Albany, New York. From this staging area, confident detachments eager for victory marched north to strategic points along the Canadian border. The Third Regiment of Artillery, commanded by Colonel Alexander Macomb, trekked thirteen days north through mud and mire, . snow and cold, past sometimes hostile inhabitants to reach their destination: “a cold and miserable place on Lake Ontario” known as Sackett’s Harbour. It was destined to become the Largest and most important American outpost during the War of 1812. During the next two and a half years thousands of troops, sailors, shipwrights and teamsters converged on this frontier village to create the nation’s most powerful wartime fleet and launch offensives to secure the conquest of British North America.

Macomb optimistically predicted:

Our next affair will be a .. fight between the fleets. The General Pike (the new ship) is fast fitting out for sea and when she is completed, a grand naval fight will decide the campaign.2

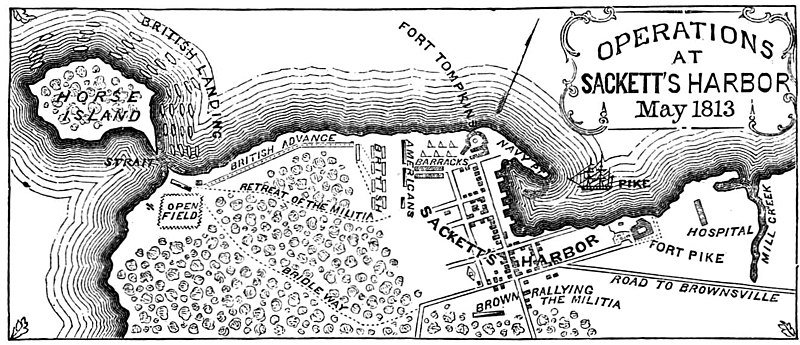

But in war, perhaps more than elsewhere in human affairs, events unfold differently from expectations. Britain responded forcefully to thwart America’s ambition to wage offensive war from Sackett’s Harbour, and by the end of 1813, events turned against these would-be conquerers of Canada. This frontier village thus became the bulwark in the defense of the northern frontier. This startling turn of events can only be understood in view of Sackett’s Harbour’s geography and the milestone battle on May 29, 1813. To understand, we begin in 1801, at the eastern end of

Lake Ontario where the powerful Black River forces its way into Black River Bay .There, a harbor is found, a harbor which is sheltered from winds and surges of the lake that soar like those of the ocean. A peninsula of limestone rock, perfectly protects a sheet of water containing about 10 acres. The land fronting this bay is raised about 30 feet and when seen from

the water, these cliffs resemble the walls of an ancient fortification.3 ·During the same year, Augustus Sacket, a New York City land speculator, learned of this deep, sheltered harbor on the edge of the primeval forests and travelled there to personally inspect the site.4 Impressed, Sacket pushed back to New York and secured title to a tract of land

1 New York State Archives, Macomb’s Orderly Book, Nov. 21, 1812.

2 Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Washington, DC. Alexander Macomb to Samuel Smith, 24 June 1813.

3 Voyage dans la Haute Pensylvanie, et dans l’Etat de New York, par un membre adoptiv de la Nation Oneida, Vol. III, p. 408. Earliest known detailed description of Sackets Harbor.

4 SACKETT, Augustus, (1769-1827), lawyer and land speculator, son of Samuel and Mary Sackett, born in New York City, November 10, 1769, and studied law, became a land speculator located mainly on or near the eastern shores of Lake Ontario purchasing a tract contained 16,500 acres. Married Minerva Camp of Catskill, and in 1801 disposed of his business interests in New York City and moved to Sackett’s Harbor, (as he spelled it). In 1805 a number of English colonists settled there. The federal government created a U.S. Revenue District and appointed Sackett its first collector.

In 1806, the township of Houndsfield, which embraced the village, held its first town meeting, and Sackett was elected

its first supervisor. In 1807 Sackett was elected Jefferson County’s first judge. Two years later, Sackett disposed of all his holdings in Jefferson County and moved to Jamaica, Long Island. In 1812 Sackett moved to Meadville, Pa., where he purchased several hundred acres of land. He returned to New York City shortly thereafter. In 1820 he move toD:\1812\Publications\Battle of Sackets Harbor\Chapter 0 Ldocx 1115/2013 I 0:13 PM

surrounding the harbor. Gathering a few hardy settlers, he returned to found a new settlement which he christened “Mr. Sackett’s Village.”5 Sacket built a refined and comfortable Georgian residence facing his harbor on Black River Bay and made plans to erect a church on the limestone bluff that “resembled an ancient fortification,” overlooking the harbor and bay.

The sheltered nature of the new settlement, its viability as a port amidst primitive overland routes and the fertility of the soil attracted newcomers. The summers were pleasant and enjoyable, but short. Land speculators, however, failed to mention the brutality of the arctic winters that last almost half a year. Newcomers from relatively temperate New England, quickly discovered what real cold and snow were, and, as time went on, only the most hardy remained. Nevertheless, growth of the little village was steady; by 1802 a traveler reported some 30 families living in the wilderness township. An advertisement in the Columbian Gazette of Utica described the surrounding land as excellent and an alluring goal to hard-working newcomers.

Eventually, thousands of settlers from New England and eastern New York began seeking lands in the wooded northern and western section of the State. These lands were formerly inhabited by the Iroquois, many of whom fled to Upper Canada following the Revolutionary War. The population of qualified voters in the township rose from a few dozen in 1801 to 226 by

1807 and by 1810 it amounted to 943.6 Slowly carved out of the forests, Sackett’s Harbour

developed into a village of elegant modern-built houses and out-buildings, generally superior to the older communities left behind to the east. From the bluff overlooking the lake… the distant islands, main land, and outlets of rivers are all beautiful, and the scene is continually enlivened with vessels and boats; while the wharves, warehouses, and stores exhibit an appearance very much resembling a sea-port on the Atlantic.7

Sackett’s Harbour was not the only settlement founded in northern New York as thousands of land-hungry settlers poured into what became Jefferson County. About eight miles distant on the Black River, Brownville also developed into a lively village. In 1798 Samuel and Jacob Brown, Pennsylvania Quakers, purchased land from the Chassanis Company on which the community was established. The first member of the family to settle there was Jacob, who arrived at the Black River country in February, 1799.

This Jacob Brown was a tall, handsome, and resourceful man, destined to emerge as one of the most famous field commanders ofthe War of 1812.8 At an early age his father suffered financial reverses, and the young Quaker tried his hand at a number of activities. He was a

Rutherford County, North Carolina, having become interested in a large tract ofland there. Within a few years he once again became interested in land in the Thousand Islands of the St. Lawrence River and returned to Sackett’s Harbor. Sackett lost money in these transactions and died from a sudden illness while enroute from Newburgh to Sackett’s Harbor in April1827 in the 59th year of his life.

5 Hough, Franklin B., A History of Jefferson County in the State of New York, from the Earliest Period to the

Present Time_(Albany: Joel Munsell, 1854) p.173.

6 By 1814 the population of the Town ofHoundsfield grew to 1,386 with 18 slaves while Jefferson County’s total population was 18,564. Hough, p.357. ·

7 Melish, John, A Military and Topographical Atlas ofthe United States (Philadelphia: John Melish, 1815) p. 18.

8 Although equal in renown to Winfield Scott and Andrew Jackson, no analytical biography of Jacob Brown exists. For a brief character sketch consult Fredrikson, John C., Officers of the War of 1812 (Lewiston NY: Edwin Melken Press, 1989).teacher briefly before moving to the Ohio Territory to work as a land surveyor. Finding the reality of frontier life less alluring than advertised, Brown returned to teaching in New York City and subsequently turned his attention to law. This he also abandoned in favor of writing political essays and avidly studying history. To hone his public speaking ability, Brown joined a debating society and soon became a prominent member.9 It is asserted, but can not be documented, that prior to settling in Northern New York, Brown was employed as a military secretary under

Alexander Hamilton.Under Brown’s wise leadership, his clan transformed its wilderness hamlet into a prosperous community. Brown, his father and brothers opened a store, built mills, and began producing potash 10 for the willing market in British North America where it could be sold and

manufactured into gunpowder for use in the ongoing Napoleonic wars raging in Europe. The Browns soon established a flourishing trade in flour, potash, and pearl ashes with Kingston, Upper Canada, as well as Montreal and Quebec in Lower Canada. It was possible to journey from Brownsville or Sackett’s Harbour as far as Kingston by boat in one day – and to Montreal

and back in about one week.11Other settlements had been created as well. South west of Sackett’s Harbour, on the shore of Lake Ontario, lay the neighboring frontier port of Oswego. Situated at the mouth of the Oswego River, it was America’s doorway to the interior of a vast unsettled continent, and connected New York City to the Great Lakes via the Hudson, the Mohawk, and Oneida Lake waterways. Oswego’s strategic location attracted settlement and commerce. A British trading post was built there as early as 1727 12 and, later, two forts were erected, one on either side of the river’s mouth.

Oswego was the scene of bloody fighting during the French and Indian Wars (1754-1763), and was briefly under French control. It functioned as a staging area for the powerful British offensive against Montreal in 1760. Recognizing Oswego’s importance, Britain, in violation of the 1783 Treaty of Paris, retained a post there until1796. A decade later, the flourishing little port of about 40 dwellings could boast shipbuilding capabilities along with a profitable salt trade carried on with other Great Lakes centers.

American development of the southern shore of the St. Lawrence River and Lake Ontario was paralleled by British settlement to the north and west in Upper Canada. By 1800, the village of Kingston, thirty-six miles distant from Sackett’s Harbour, had already developed into the largest community on Lake Ontario. Established on the site of the former French fort

‘Frontenac’, Kingston developed as a result of the transfer of the Crown’s military facilities from nearby Carleton Island. This had been Britain’s most important military post in the Great Lakes system during the Revolutionary War. But because the 1783 peace treaty ending the Revolutionary War, placed the boundary between British North America and the United States in the middle of the Great Lakes and down the St. Lawrence River through its main channel, Carleton Island fell into American territory. During that war, the Crown constructed a dock-yard,9 Nafis and Cornish. The Life of General Brown (New York: P.J. Cozans, 1847) p.15.

10 A potassium carbonate made from wood ashes used in agriculture as fertilizer or industry as gunpowder.

11 Taylor, Rev. John, Missionary Tour through the Mohawk & Black River Countries in 1802, Vol. III. p. 70.

12 Mohar, Ronald E. “Development of Oswego’s First Settlement,” Unpublished, October 1992.The Battle of Sackett’s Harbour Chapter 1 Page 3

supply base and fort on the island. Indian and Loyalists raids were launched against the

American rebels and refugees loyal to the crown sought refuge there .After the Revolution, the British kept a small garrison on the island refusing access to Americans. By the end of the 1780s, troops, dock-yard workers, naval personnel, loyalists and Indians resettled at I(ingston taking advantage of its excellent harbor. Over the course of the

1790s, a rapid increase in population took place as refugee loyalists and American settlers seeking cheap crown lands converged on this new settlement, building houses, grist and saw mills. By 1806, Kingston contained barracks for troops, a hospital, storehouses, an Anglican church, and about 150 dwellings. Four years later, the new village had one of the largest

newspapers in Canada, the Kingston Gazette, and a thriving shipyard.13Kingston, like Sackett’s Harbour on the American side, prospered from growing trade on Lake Ontario. Being situated at both the head of the Lake and the source of the St. Lawrence river, Kingston was also the main base of the Provincial Marine. The Provincial Marine was a small offshoot of the Quartermaster’s Department used to transport troops and supplies to British garrisons throughout the Great Lakes. A position in the Provincial Marine required little or no effort, as captains of its vessels were aging septuagenarians with limited combat experience .

Two new warships, the Duke of Kent and the armed schooner Duke of Gloucester, were built to augment those constructed during and shortly after the Revolutionary War. 14 Lake seamen enrolled as volunteers and were trained in naval gunnery. In 1809 a twenty-two gun corvette,

Royal George, was launched. She was the largest ship of war built to date on the fresh water interior of North America, and a stern reminder of British military presence.Most Americans; however, ignored military developments and one newspaper wrote:

Upper Canada was considered the most temperate climate as well as the most fertile soil, belonging to the British in Canada. The rapid improvements in agriculture, and the advancement of manufactures, are justly attributed to the activity and enterprise of the American farmers,· who from grants of crown lands, have been induced to settle in great numbers in that province. Indeed Upper Canada would be considered as a territory belonging to the United States from the

immense difference which exists between the industry of its inhabitants and those of Lower Canada (French Quebec)- from their manners, habits, and appearance- and from the value of their farms and the luxurious appearance of their crops.15As the border communities consolidated and grew in population, trade between them boomed. Soon, scheduled travel between Sackett’s Harbour and Kingston was arranged. Upwards of forty small merchant schooners were built on Lake Ontario to carry wheat, flour, beef, pork, lumber, and other commodities to Canada. There these commodities were traded for

quality British manufactured goods difficult or impossible to procure on the American frontier. 1613 H. Niles, Editor, The Weekly Register (Baltimore: Franklin Press, 27 June 1812), p.288.

14 Preston, Richard A., Kingston Before the War, A Collection of Documents, The Champlain Society for the

Government of Ontario, (Toronto ON: University of Toronto Press, 1959) p. lxxxvi.

15 Niles’ Weekly Register, June 27, 1812. P. 288.

16 John Melish, A Military and Topographical Atlas of the United States; Including the British Possessions &

Florida (Philadelphia: John Melish, 1815), p.19.Inevitably, such a flourishing business attracted the attention of revenue-hungry Washington and in 1803, Sackett’s Harbour was designated the sole customs port between Oswego and Ogdensburgh17 on the St. Lawrence River. Augustus Sacket, the most prominent local member of the community, was appointed the first customs agent of the newly established Sackett’s Harbour District. But as time went on, the threat of war between the United States and Great

Britain overshadowed the prospects of continual prosperity between the Harbour and the other peaceful border communities .The mounting tension between the two nations resulted from the very treaty which ended the Revolutionary War, the Treaty of Paris, because it failed to establish a route to develop amicable relations between the United States and Great Britain. Both countries violated terms of the treaty and, in particular, the crown refused to relinquish her posts on the northern territory of the new republic, including Oswego, until Jay’s Treaty of 1794 brought a temporary lessening of antagonism. One clause stipulated that Great Britain would withdraw her forces from these posts. The crown did obey treaty stipulations with the exception of Carleton Island. It was a minor sticking point but greater friction arose on the northwestern frontier of the then United States .

As the pioneers pushed westward, the Indians of the Old Northwest formed a confederacy to resist white encroachments. Determined to defend their land, the tribes appealed to their former ally, Great Britain, for assistance. The British were careful to appear neutral in the resulting conflict, but many Americans suspected British sympathies lay with the Indians and that they were secretly encouraging the uprising .

A more serious irritant arose from the world war Britain had waged virtually without cessation against France since 1793. This conflict created a demand in Europe among both belligerents for American raw materials. Consequently, the American merchant marine experienced phenomenal growth and, since the need for crews could not be met at home, American carriers began drawing on the skilled human resources of Britain. It is estimated that, in the first decade of the nineteenth century, between fifteen and twenty thousand British sailors

deserted the Royal Navy, many to sign on with American merchant ships. 18 Not only was

treatment more humane but they were also fed, paid and berthed in better conditions.Britain acted decisively to prevent the hemorrhaging of trained seamen both from her navy and merchant marine. Her warships actively stopped American flag vessels under “the right of search” and impressed any sailors they suspected to be British. Although American seamen were issued identification papers, the Royal Navy often refused to recognize them and, according to official complaints lodged with the Department of State, 6,257 American citizens were

impressed into the Royal Navy prior to April, 1812.19 Washington made strenuous efforts to get

them back, but many Americans languished in the lower decks of His Majesty’s warships for years.17 I have chosen to use the earlier spelling (Ogdensburgh), rather than the modem (Ogdensburg), except when quoted.

18 Niles’ Weekly Register. Vol. II, March 1812-September 1812.

19 Niles’ Weekly Register, Ibid.In the course of developments, America became caught between both belligerents as both Britain and France passed decrees forbidding neutral nations from trading with the other. Since the Royal Navy ruled the seas, the British prohibition– the 1807 Orders-in-Council –weighed more heavily on the United States than did those of France. British warships enforced the Orders and violators were subject to seizure. Congress, at the behest of President Thomas Jefferson, enacted an embargo in 1807 stipulating that no clearance should be issued to American flag vessels bound for any foreign port. It was a ploy intended to force the warring powers of Europe to show greater respect for the rights of neutrals and to keep the United States from becoming entangled in a foreign war.

The results were both predictable and unsavory. American cotton, tobacco, and other goods rotted on wharves, the merchant marine was laid up, seamen were unemployed, and prices plummeted. The American economy went into a recession in 1808 for which public sentiment blamed Britain. The Embargo Act, designed to keep the United States out of war, only succeeded in pushing her to the brink.

The embargo applied equally to the Great Lakes as well as the Atlantic trade, and succeeded in dashing the thriving prosperity of northern New York border settlements. Not surprisingly, smuggling, especially of potash, became rampant. The illegality of exporting it from American ports led to extensive and systematic measures to transport it to Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River. This commodity fetched between $200 and $300 per ton in Montreal and from that city, there was no obstacle in exporting it to England.

In an effort to evade the embargo, Americans transported potash and other goods which sometimes “vanished in the night” or were transported with due formality to Ogdensburgh where they simply “disappeared,” or were shipped in open defiance of the law. Naturally, these commodities were sure to magically reappear in Montreal to the great profit of those transporting them. To check this illegal trade, the State and Federal governments took the unpopular step of stationing troops at Sackett’s Harbour and other northern ports.20

In August 1808 the Oswego customs collector seized a shipment of Canadian flour that had been smuggled into the port. A few days later sixty armed men boldly announced their intention to recapture the flour. They swaggered through the town, uttering threats that they intended to attack the customs house and “clear out the town or burn it.”21 The customs collector sent a courier to alert a troop of New York State militia dragoons stationed nearby. The unit

commander saddled his outfit and rode toward Oswego. Upon hearing the sounds of galloping horses, the insurrectionists fled into the nearby woods and made their way home as best they could?2New Yark’s military-minded Governor Daniel Tompkins believed it was necessary to “suppress the existing insurrection and to aid the Collector to carry into effect the Laws of the United States against the armed and violent resistance made at said port.”23 As commander-in-

20 Hough, History of Jefferson County, p.458.

21 Public Papers of Dania! D. Tompkins, Governor ofNew York 1807-1817. Published by the State ofNew York, Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co., State printers, New York and Albany. 1898. Military -Vol. I, p. 196.

22 Ibid, p. 196.

23 Ibid. Daniel Tompkins to William Paulding, Lt. Col. and A.D.C. Headquarters New York, 19th August, 1808.chief of the State Militia, he ordered militia detachments to Oswego and protect the port from any new outbreaks of violence emphasizing that:

If it should be found impracticable … to reclaim from their errors those deluded citizens who have wickedly indulged themselves in violations of their civil obligations, by armed and forcible opposition to the execution of the Laws, then force must be employed to rescue the insulted laws from the violence of these offenders, to suppress the existing Insurrection and to prevent any armed or forcible arrest and removal of vessels or property legally detained or seized by the

Collector of the district of Oswego.24The same month at Sackett’s Harbour, Hart Massey replaced Sacket as customs agent. During the next winter on March 14, 1809, a distressed Massey reported: “Nature has furnished the smugglers with the firmest ice that was ever known on this frontier.”25 The sleighs of the smugglers passed Sackett’s Harbour ten miles from shore, and available forces were insufficient

to stop them. Smugglers were determined to evade the laws even at the risk of their lives. At Ogdensburgh, they even conspired not to allow a government force to be stationed in that vicinity. The smugglers threatened that if any officer of the law should interfere they would take a raw hide to them. “These threats don’t terrify me,” Massey remarked, “I only mention them to let you know their unprincipled determination.”26 The smugglers and the militia stationed there

to patrol the border eventually developed a mutual understanding. The inexperienced troops simply looked the other way in exchange for being left alone.Normally the militia assigned to patrol duties received little training and served only short periods of time. Their officers were largely political appointees, and when they did turn out for duty, it amounted to little more than political rallies, parades and drinking binges. 27 Massey found it almost impossible to get any assistance from the intimidated militia to move confiscated

contraband to government storage. He felt if he did not have his own armed men with him, the inhabitants would “assemble in the night and take the property…” Some people supported the law but were fearful of fulfilling their legal obligations. Massey exclaimed; “My life and the lives of my deputies are threatened daily. What will be the fate of us? God only knows.”28Jacob Brown of Brownville was alleged to have been one of these smugglers. A road known as “Brown’s smugglers road” was cut through the forest from the Black River to French Creek and north toward the St. Lawrence River. This road became a major thoroughfare for smugglers making their way to Canada. Brown plied his illicit trade so diligently that he accrued considerable wealth and acquired the inglorious title of “Potash Brown,” a nickname his enemies would revel in.29 Intelligent and enterprising, Brown not only developed his family’s new settlement, but in 1809 he also managed to secure appointment as lieutenant-colonel

24 Ibid. Daniel Tompkins to William Paulding, Lt. Col. and A.D.C. Headquarters New York, August 19, 1808.

25 Hough’s History, p.459.

26 Hough’s History, p.459.

27 White, Jeffersonians, p.534-35. James Ripley Jacobs, The Beginning ofthe U.S. Army, 1783-1812 (Princeton: 1947), p.381-82.

28 Hough’s History, p.459.

29 Landon, Harry F., Bugles on the Border (Watertown NY: Watertown Daily Times, 1954) p.12.(commandant) of the newly formed 108th Infantry Regiment, New York Militia.30 In 1811

Governor Tompkins was searching for a suitable candidate to fill the vacant position of Brigadier-General on the vulnerable northern frontier. Because political infighting cancelled out two leading contenders, Tompkins decided to appoint 36-year-old Brown instead.31Many felt the Governor’s choice was a good one as Brown maintained an active interest in military affairs. Brown wanted a militia capable of effective active service, but could he get it on the frontier where many other settlers were also part-time smugglers? On the contrary, in order to remain popular with the local militia, Brown limited expenditure of time and money for parades and other time-consuming military musters. This was a difficult balancing act. In a frontier society, planting and harvesting crops, clearing forests and building adequate shelter were foremost on people’s minds. The last thing the rank and file of the militia wanted to do, was

waste time and money on what they considered as unpopular and frivolous military service .The Federal government struggled to cope with the smuggling crisis by sending more troops north and building a warship at Oswego. This task was given to twenty-six-year-old, Lieutenant Melanchton T. Woolsey, USN, who received orders to superintend the construction of the gun brig on Lake Ontario and two gunboats on Lake Champlain. Woolsey, a navy career officer since

1800, had already distinguished himself in the Quasi-war with France and the Tripolitan Wars.Military service seemed to run through Woolsey’s family. His father had been a prominent but controversial officer in the Revolution and his mother was a member of the powerful Livingston family. Woolsey’s grandfather had been an officer in the British army during the French and Indian War and was killed in the campaign against the French at Ticonderoga. Young Woolsey, attentive to detail and capable of following instructions implicitly, was the Navy’s ideal choice for this arduous duty .

Before departing New York for Oswego, Lieutenant Woolsey notified the Navy Department that it was impossible to secure good workmen and most building materials on Lake Ontario. He had learned that even the British were compelled to hire carpenters from the New York ship yards to build a newly completed vessel at Kingston. Woolsey sought to ease his task by contracting noted ship designer Christian Berg and master builder Henry Eckford “as they are said to be the most faithful workmen.”

Born and raised in the shipbuilding region of Hamburg, Germany, Berg had earned a reputation as one of New York’s leading shipbuilders because of advanced designs and the quality of his vessels. The thirty-three-year-old, Scottish-born Eckford began his trade in the shipyards of Quebec under the apprenticeship of his uncle, the eminent naval builder, John

Black.32 By age 21, Eckford left Canada and owned his own shipyard inNew York. He was soon

recognized as one of the foremost shipbuilders in that city and his carpenters were considered30 Lyon, James B., ed., Military Minutes of the Council of Appointment of the State of New York, 1783-1821 (Albany

NY: State ofNew York) Vol. II, p.l079.

31 Public Papers of Daniel D. Tompkins, 1807-1817, Vol.II, pp.403-409.

32 Jefferson County historical society, American Mechanics, Henry Eckford. p.211-215. (Date unknown).

among the best available. Woolsey closed the contract and began what was to become a long and enduring ship-building relationship with Henry Eckford.33

On August 6, 1808, Lieutenant Woolsey and Sailing Master34 Thomas Gamble, USN, departed New York for Oswego followed by Eckford and a gang of workmen. They were later joined by midshipman James Fenimore Cooper, USN, a young man with a literary bent. Woolsey and Gamble reached their destination on the evening of the 12th, while Eckford and company

I

arrived the following morning. He brooked no delay in organizing his men to construct quarters

I

I and prepare a dockyard on which to frame the gun brig.

i

Woolsey, however, was alarmed by military conditions at Oswego because it lacked a garrison of regulars under the direct authority of Washington. Taken aback, he wrote Washington that “there is much to be apprehended from the turbulent spirit of the people in that

part of the country, who… are infringing on the Embargo Laws” and suggested that a detachment of marines be sent to protect the dockyard.35 The young officer was singularly unimpressed by Oswego which he described as:A rather dreary place perfectly destitute of genteel society, many of the necessities and ALL of

the luxuries of life. Messieurs Gamble, Cooper, and myself are, however, tolerably well quartered and in hopes with what we shall be able to procure from the east to weather out this winter pretty comfortably. Mr. Gamble, Cooper, and myself yet enjoy good health.. for this is the most dreary hole at this season I ever saw.36Under Eckford’s aegis, progress on the gun brig was rapid and, by September, Woolsey reported that most of her timbers were prepared, the keelson and all the top timbers were of the best white oak. Early winter found the frame of the brig complete, the planking had begun and the rigging, rails, cables, and anchors en route from New York. Woolsey requested permission to

37i I replace the heavy 32-pounder.

long gun planned for the new vessel with two, much lighter 24-pdr. short-barrelled carronades because he feared its weight would render the brig “truly laborsome for this Lake, as the sea here is much shorter than on the ocean.”38 Although he confessed that he was initially pleased with the idea of mounting a heavy gun in the bow, he now doubted its practicality for there was “not a more ferocious sea in the world than Lake Ontario.” He feared the brig would be swamped in heavy seas, so lighter armament was in order. Woolsey

was also concerned about Oswego’s viability as a base for the new vessel. During the summer months, the level of Lake Ontario fell, making it risky for the deep drafted brig to sail because of a shifting sand bar in the river mouth. Upon investigating he discovered there were only two33 Burton Historical Collection. “The Woolsey Family Papers 1809-1815”. Detroit Public Library Microfilms

(University Microfilm & Company, February 1969). (Hereafter cited: Burton Historical Collection).

34 Rank in U.S. Navy, equivalent to warrant officer today.

35 Burton Historical Collection. Ibid.

36 Burton Historical Collection. Ibid.37 Artillery was classed according to the weight of the projectile fired, i.e. a six pounder fired a six lb. cannonball; a

32 pdr. fired a 32 lb. cannonball, etc.

38 Burton Historical Collection. Ibid.anchorages on the American side of the lake, Sackett’s Harbour and the Niagara River, which could accommodate his vessel.39

Eckford’s carpenters made swift progress and the new brig was launched March 31, 1809. A proud Woolsey described her as “the handsomest vessel in the Navy.”40 Since he had received no instructions what to name her, he decided to proclaim the brig “Oneida, after the country in

which she was built, a lake in the vicinity of this place, and a nation of Indians that inhabit the border ofit.”41 Shortly thereafter, Woolsey sailed to Sackett’s Harbour to explore the possibility of establishing a navy yard there. He reported the peninsula forming the harbor had from 10 to

13 feet of water and was within 150 yards of the place best suited for a public dock. Woolsey also recognized that the limestone cliffs resembling “the walls of an ancient fortification,” dominated the harbor and bay. Here, he believed a battery could be built to mount the brig’s guns in winter. Woolsey concluded, “I think it is the only place suitable on the American side for establishing a navy yard.”42By December 1810, the Oneida and its skeleton crew were transferred to Sackett’s Harbour with orders to suppress smuggling and conduct other revenue duties. Woolsey thereupon commenced construction of a guardroom, a boat house, and a mess room to accommodate them. Augustus Sacket’s plan to build a church on the bluff never materialized because his sheltered anchorage was slowly becoming the U.S naval headquarters on Lake Ontario.

As Woolsey busied himself, the United States and Britain continued their inexorable drift towards war. American passions were further inflamed in 1807 by the Chesapeake Incident. The British warship, HMS. Leopard, encountered the US.S. Chesapeake off the Virginia capes and demanded that a boarding party be allowed to search her for British deserters.43 The American captain refused and was fired upon with three broadsides. The Chesapeake, not properly outfitted

and with a new crew, surrendered. The British boarded and took off four alleged deserters, one

of whom they hanged. As a result of a national outrage, the British offered to pay reparations and return the other three. This, more than any other single incident, ignited anti-British feelings that swept across the United States.44Tensions were also rising on another front. Many Americans, especially frontiersmen, felt it imperative to occupy British North America before settlers could be free from Indian hostility. The cry, “On to Canada,”45 spread from local taverns to the halls of Congress and from

newspapers to pulpits. The cry was directed against a perceived threat of an unholy alliance between the British and the Indians. One newspaper commented;39 Burton Historical Collection. Ibid.

40 Burton Historical Collection. Ibid.

41 The use of the word “country” in early 19th century language correlates with the word “territory” or “region” today.

42 Burton Historical Collection. Ibid.

43 Great Britain did not recognize the right of British deserters to become naturalized Americans. The saying was: “Once an Englishman, always an Englishman.”

44 J. Fenimore Cooper, History of the Navy of the United States, Vol. II (New York: Blakeman & Mason, 1864). p.15-20.

45 Niles’ Weekly Register. May 30, 1812. p.209.It is essentially necessary that Upper Canada should be the object of attack, in order to exterminate, at one bold, determined blow, the horde of remorseless savages and their inhuman abettors, whose massacres and barbarous murders have lacerated the feeling heart, and aroused the vengeance of an injured country.46

Furthermore, some Americans harbored a growing fear that Canada would serve as a base for

British encroachment southward into the interior of the continent, girdling the United States to the Atlantic seaboard. The conquest of Canada could be of supreme importance “to us in distressing our enemy” by cutting off provisions and naval stores for their West India colonies

and beyond.47 Many Americans believed the only way to bring about eventual peace was through

expulsion of the British from Canada and creation of a North America free from foreign influence. As a pro-war, nationalistic newspaper declared, war with Britainwould have a powerful effect in weaning the people of the United States from what some yet regard the mother country…It will teach our citizens a most important truth,… that they have a country; and cause them to look to themselves, instead of extending their views across the Atlantic, for sources of happiness.48

By December 1808, it seemed the United States was on the brink of hostilities with Britain. President Jefferson assumed that British military forces garrisoned at Halifax were ready to sail to the West Indies and from there threaten New Orleans if American troops invaded Canada. Both he and his cabinet calculated that the British intended to hold New Orleans as a bargaining chip for whatever territory might be lost by such an attempt. Jefferson decided to reinforce the vulnerable American defenses on the Mississippi and ordered the disreputable, 51- year-old, Major-General James Wilkinson, commandinthe Southern Department, to assemble

his troops near New Orleans to repel any British threat. 9Wilkinson, ostentatious and of enormous presence, had developed a reputation for intrigue with the Spanish in Mexico. As an accomplice of the equally disreputable Aaron Burr, he had lent a favorable ear to Burr’s dazzling schemes to invade Mexico and create their own “republic” independent of the United States. When the cabal fizzled, he professed innocence and turned witness against his erstwhile colleague. Jefferson, perhaps against his better judgment, still entrusted this shadowy figure with high command .

Not all the officers accompanying this mission were so disreputable. Lieutenant-Colonel Electus Backus formerly commanded the 4th New York Militia Regiment of the upper Hudson region.50 He entered regular service in 1807 and rose rapidly in rank. With his regiment, the 1st

46 Niles’ Weekly Register. Vol. II. June 27, 1812. P.288.

47 Niles’ Weekly Register. Vol. II. March 1812- Sept. 1812.

48 Niles’ Weekly Register. July 18, 1812. P.331.

49 James Wilkinson. Memoirs ofmy own Times, Vol. II. Philadelphia: Abraham Small, 1816. P. 342. Ibid, pp.340-

525. As a result of inadequate supplies and mismanagement approximately 300 soldiers died of disease between

Terre aux Boeuf and Natchez, for which Wilkinson was court martialled.

50 BACKUS, Electus (ca. 1768-1813). American military hero. Born in Connecticut but at an early age moved with his family to New York state. At the age of 14-15, he served in the Revolutionary war as a volunteer seeing action on the Hudson River against British troops near Peekskill, New York. The action was insignificant but showed his proclivities toward his country. Backus served in the New York State Militia until joining the U.S. First LightThe Battle of Sackett’s Harbour – Chapter 1 Page 11

._j

Light Dragoons, Lieutenant Colonel Backus arrived at New Orleans in May 1809 to partake of the military build-up in Louisiana. Wilkinson, with the 3rd, 5th and 7th Regiments of Infantry, some 1,542 men, ordered Backus to encamp at the low and swampy grounds of Terre aux Boeufs. Col. Backus made an attempt to drain the encampment but failed because of inadequate supplies, spoiled rations, and mosquito-infested swamps.

Within a few weeks more than 1,000 men became ill, deserted or perished. Attempting to preserve the demoralized Army, Backus moved the surviving troops to higher grounds at Natchez, while Wilkinson remained safely quartered in New Orleans accompanied by one of his favorite Creole beauties. Brigadier General Wade Hampton, who personally detested Wilkinson, ordered Backus to Washington to explain what went wrong. The testimony he provided caused Wilkinson to be charged with irregularities in his accounts, namely, with having purchased

inferior goods and pocketing the difference.5 1Backus then served as one of the prosecution’s chief witnesses in the 14-month long court martial proceedings. With considerable skill, Wilkinson convincingly placed the blame elsewhere and was acquitted. A senior, if sinister figure, he would in time wreak more havoc on the fledgling American army.

War did not erupt in Louisiana but in the prevailing political atmosphere Great Britain’s tentacles were seen lurking everywhere. By the end of 1811, this distrust and hostility reached a fever pitch in Congress and Henry Clay, Peter B. Porter, John C. Calhoun and other War Hawks clamored for increased military preparation and insisted the time had come to strike a blow for “honor and country.” Accordingly, the demoralized regular army was to be increased by 10,000 men, while the states were to provide 50,000 volunteers for federal service. 52

If needed, state militias were to be mobilized, the navy strengthened with armed merchant ships and privateers provided with “Letters of Marque.”53 Yet, opinions respecting the drift

4towards war were far from unanimous. The Federalists,5

particularly those from New England,feared the nation might not survive a prolonged contest with the world’s leading naval power. An article in Nile’s Weekly Register of Baltimore proclaimed:

Dragoons as Major on Oct. 7, 1808. He advanced to Lieutanent-Colonel Feb. 15, 1809. He served under Gen. James Wilkinson at Camp Terre aux Boeufbelow New Orleans, whose army was decimated by disease, death and mismanagement until it was forced to relocate to Natchez. Backus was one of the many taken ill, returning to his wife and ten chlidren at Greenville, New York (Green County) the following year to convalesce. He was subsequently a witness in the case against Wilkinson. At the begining of the War of 1812, he assembled with the troops of his regiment at Pittsfield, Mass., and marched them to Sackett’s Harbour, New York where the remainder

of this investigation takes place. Duke University, Durham, N.C.; Special Collections Department, William R. Perkins Library; Electus Backus Papers, Detroit, Mich; February 1, 1860.

51 Wilkinson Memoirs, Vol. II. P.340-401.

52 Niles’ Weekly Register. July 11, 1812. p.318.

53 A “Letter of Marque” authorized a privately owned, armed merchant ship to seek out and capture enemy merchant vessels, a percentage of the value of the capture would go to the government, the remainder to the ship owners, officers and crew.

54 One of the two main American political parties of the period favoring a strong centralized national government and amicable relations with Great Britain. (nicknamed the “English Party,” by the press).A Declaration of War would be in effect a license and a bounty offered by our government to the British fleet to scour our coasts — to sweep our remaining navigation from the ocean, to annihilate our commerce, and drive the country into a state of poverty and distress…The proposed enemy is invulnerable to us, while we are on all sides open to assault. The conquest of Canada would be less useful to us than that of Nova Zembla,55 and could not be so easily achieved.56

Others, especially the Democrat-Republicans57, argued France would triumph over England in Europe, hence now was the time to settle scores with Great Britain. As the national debate continued, attention shifted not on whether war was to be declared but on how it was to be

waged.58On paper, if not in reality, the conquest of Canada appeared deceptively easy. About 7,2 million people lived in the United States of 1812 compared to only 650,000 in Upper and Lower Canada combined. The United States army was authorized at 11,700 regulars of all ranks; however, only some 6,700 could be mustered. These troops were under the command of two major generals, Henry Dearborn and the aging Thomas Pinckney, but a functioning chain of

command had yet to materialize.59 Strategy-making was an ad hoc arrangement that involved the

President, the Secretary of War, Army and Navy, as well as the senior field officers and naval commanders. Their roles were never properly defined or understood, therefore, military policy was almost totally lacking in coordination and strategy .During the summer of 1812 the British had about 7,000 regular troops to defend Upper and

Lower Canada. Out of a global force of250,000, this was a mere fraction of their strength. Of

11,000 militia in Upper Canada only 4,000 were considered trustworthy; the rest were recent immigrants from the United States. Governor Tompkins predicted that as many as “one-half of the militia would join our standard.” According to Congressman Peter Porter from western New York, “Canada possessed only a force of 6,000 regulars stationed at Quebec, and about 20,000 militia, not well organized, armed or disciplined.” 60With Great Britain threatened by Napoleon, a military campaign· to seize Canada seemed a mere matter of marching. But the warhawks failed to realize that the American militia would have been a useless component of an invading army because of a lack of discipline, poor equipment, and unresolved constitutional questions regarding chain of command and whether it could be even be deployed outside respective state borders. Because of the absence of national

55 A barren, uninhabited island north of Russia near the Arctic Circle.

56 Niles’ Weekly Register, Vol. II, p.207.

57 One of two major American political parties. Favored strict interpretation of the Constitution to restrict the powers of the federal government, emphasized states rights and close relations with France. (nick-named the “French Party” by the press).

58 For an in-depth understanding of the road to war, J.C.A. Stagg’s Mr. Madisons War, Politics, Diplomacy, and

Warfare in the Early American Republic 1783-1830, is indispensable.

59 J.C.A. Stagg, “Enlisted Men in the United States Army, 1812-1815: A Preliminary Survey,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser. 43. October 1986. An estimated 7,000 troops were available to defend Upper and Lower Canada during the Summer of 1812, according to a general return of troops in Cruikshank’s, Niagara Frontier.

60 Niles Weekly Register, Feb. 22, 1812. p.459.draft laws, most militiamen served under the authority of state governors. Even if this had not been the case, constitutional, financial, logistical, and tactical considerations ruled out the creation of a mass citizen-army. To be capable of defeating the tough, regular British Army in Canada, the tactics of the time called for a well-trained army and navy deployed on the frontier and ready to move. Such a force, however, was lacking in the political, economic, ideological, and social environment in the United States of 1812.

Military tensions along the northern frontier worsened. With the passage of the Embargo Act, a detachment of American troops under Lieutenant Joseph Cross, Regiment of Artillery, was posted at Sackett’s Harbour in 1808. Lieutenant Cross informed British authorities at Kingston that he planned to station troops at Carleton Island. In response the British replied they intended

to retain possession of the island and sent a reinforcement to strengthen the post. Instructions were given to the garrison that if the Americans seized it, no counter-attack should be made; the settlement of any such incident should be left to negotiations between the two governments .As relations with the United States deteriorated, a party of Royal Engineers was dispatched from Kingston to Carleton Island in the summer of 1808 to destroy a number of guns or bring them back to Kingston. Because the guns were so heavy and difficult to move, the engineers

sank them in deep water where they could not be easily recovered.61Next, the British took steps to erect a blockhouse in Kingston. The construction program and the growth of the fleet made K.ingston a more vital area than ever before. Meanwhile, the Royal George, laid up in 1811, had her armament mounted early in 1812. In the event of war, one swift blow by an American force against Kingston, the British realized, could destroy British naval supremacy on Lake Ontario and thus jeopardize all of Upper Canada. Consequently, they took steps to prevent this from happening.

In the spring of 1812, Major General Dearborn promulgated a plan to invade Canada.62 This distinguished, but now heavy, unwieldy-looking veteran of the Revolutionary War proposed to61 National Archives Canada. c.527, p.83. Mackenzie to Lt.-Col. Green. Kingston, Aug. 24, 1807.

62 DEARBORN, Henry (1751-1829). Born at Hampton, New Hampshire (February 23, 1751), the son of Simon and Sarah Dearborn; studied medicine and established a private practice (1772) and joined the state militia; as a captain, he led his company to Boston after Lexington and Concord (April1775), and served in Benedict Arnold’s ill-fated expedition to Canada, but was captured at Quebec (December 31) and spent nearly a year on parole before he was exchanged and could rejoin the army (March 10, 1777); promoted major (March 19), he fought under Gen. Horatio Gates at Ticonderoga and at Saratoga (September 19), at which time he was promoted Lieutenant colonel; after Valley Forge, he distinguished himself Monmouth (June 28, 1778); served in the Sullivan expedition against the Iroquois and their Loyalist allies in Pennsylvania and central New York (May-November 1779); as a colonel, he served at the siege of Yorktown (September 28-0ctober 17, 1781), and was discharged from the Army (June 1783); settling in the district of Maine where he was active in the Massachusetts militia, rising to brigadier general (1787), then major general (1795); member of the House of Representatives (1792-1797); as Secretary of War under Democrat-Republican Thomas Jefferson (March 1801), he ordered the establishment of a post, called Fort Dearborn, at what is now Chicago (1803); left the cabinet (March 1809) and became the collector for the port of Boston, but was recalled to active duty by President Madison as senior major general in command of the northern frontier (January 1812); this book you are now reading explains Dearborn’s involvement in the War of 1812 until he was relieved of his command in July 1813. After the War of 1812, he served as minister to Portugal (1822- 1824); retired on his return and died at Roxbury, Massachusetts near Boston June 6, 1813. As a young officer, Dearborn was courageous and able, but his period in command ofthe northern frontier in the War of 1812 was marked by delay, miscalculation, and a lack of competence and sound judgment.establish headquarters near Albany, granting easy access to Lake Champlain, Sackett’s Harbour and the Niagara frontier .

Once war broke out, Dearborn would conduct the main advance against the strategic city of Montreal by way of Plattsburgh on Lake Champlain. With the capture of that important city, British forces in the Great Lakes area to the west would be cut off from military supplies and reinforcements. The enemy would then have little recourse but to capitulate. Simultaneously, other armies, primarily composed of militia, were to invade Canada from Detroit in the Michigan territory and across the Niagara River from New York State into Upper Canada .

The U.S. Navy, meanwhile, was to create a fleet to insure control of Lake Ontario. This accomplished, units could be transported across the lake to capture British Headquarters at Kingston. Once United States forces controlled Upper Canada, Dearborn felt the Indians would quickly be subdued. Dearborn had developed what appeared to be a sound plan, at least on

paper.63Waging war is very difficult, but the difficulty is not that erudition and great talent are needed… there is no great art to devising a good plan of operations. The entire difficulty lies in this: To remain faithful in action to the principles we have laid down for ourselves. Von Clausewitz.64

If one believed the rhetoric of the Democrat-Republicans, there would be no lack of enthusiastic volunteers available for the conquest of Canada. Thirty-three-year-old New Jersey native, Lieutenant-Colonel Zebulon Montgomery Pike, was one offering to serve on an expedition to Canada.65 Pike, a career officer since 1799, and an early graduate of West Point, was an aggressive and professional soldier who evinced concern about the training and welfare of his troops.66 He had already gained fame for his explorations of the Mississippi and New Mexico territories. Because of this renown, he was an officer who could be envisioned as a herald to arouse the nation’s spirit for the war effort. In time, his name would become symbolically associated with Sackett’s Harbour.

63 Cruikshank, A Documentary History of the Campaign on the Niagara Frontier, 1908. Vol. I.

64 Karl Von Clausewitz, 1780 – 1831. Prussian general and military strategist who defined principles of war.

65 U.S. National Archives, Washington, D.C. RG 107, Microfilm series M221-47 Letters Recieved by the Secretary of War. #2426. Pike to Eustis, March 27, 1812.

66 PIKE, Zebulon Montgomery (1779-1813). American General and explorer. Born Lamberton, (near Trenton) New Jersey, the son of an army officer, entered his father’s company of the 2nd Infantry Regiment as a cadet at age fifteen, and was commissioned a Lieutenant (November 1799); served on the frontier and was sent by Gen. James Wilkinson, governor ofthe Louisiana Territory, to affirm U.S. claims to the Mississippi River (1805); while on that expedition he reported (incorrectly) that Leech Lake, Minnesota, was the source of the Mississippi River; he also told Indian leaders they must accept U.S. rule, and warned the British that their presence in the territory was a violation ofU.S. territorial rights; Wilkinson then sent Pike south to gain information about the Spanish territories and locate the source of the Red River (1806); the expedition became lost and spent much time trying to climb

Grand Peak (later renamed Pike’s Peak) and exploring Royal Gorge in present day Colorado; the expedition followed the Rio Grande into Spanish territory, was captured and taken to Santa Fa (1807); Pike was released and returned to St. Louis to fmd himself embroiled in the Arron Burr and Wilkinson conspiracy to create an empire in

the southwest. Pike was cleared of all charges by Secretary of War Henry Dearborn; this book explains Pike’s role in

the War of 1812.Once war broke out, it would be folly to contend with Britain on the high seas. The United States with its Lilliputian fleet of 20 warships, only one of which, the Oneida) was on Lake Ontario, and 170 fragile and useless gunboats, was no match for Britain’s 994-ship navy.67 It was

foolish to believe the U.S. could invade the British Isles, (though Jefferson had at one time considered hiring arsonists to torch British cities).68 The U.S. possessed several well-constructed frigates, all on the Atlantic seaboard that were superior to similar class British ships, but they

were no match for the numerous and powerful British ships-of-the-line.The task assigned to the U.S. Navy on Lake Ontario was a difficult one. Here Britain’s naval force consisted of five ships and schooners mounting a total of 70 guns.69 Lieutenant Woolsey dispatched from his new base at Sackett’s Harbour a list of these vessels and their probable

armament to Navy Secretary Paul Hamilton.70 The largest vessel was the Royal George) with

twenty-two 18-pdr. carronades; the Earl of Moria) to carry fourteen 9-pdr. long guns; the schooners; the Duke of Gloucester, twelve 6-pdr. long guns; the Simcoe, fourteen 6-pdrs; as well as two or three more schooners capable of eight 6-pdr.long guns each. He was under the impression that only the Royal George was equipped, officered, and at least partly manned. Furthermore, Woolsey learned that authorities in Kingston were making preparations for the defense of Upper Canada and that a number of guns had recently been shipped there .Woolsey then created a list of American merchant vessels on the lake capable of being pressed into service in the event of war. The largest, the Charles and Ann, he hoped, would carry twelve 18-pdr. carronades. Two smaller schooners, the Fair American and Diana at Oswego, as well as, the Niagara and Ontario at Fort Niagara, and at Ogdensburgh, the Collector,

Experiment, and Genesee Packet would all be armed with long 6-pdrs. Besides these, there was

the schooner, Julia, of about 50 tons, that had been recently launched at Oswego. Woolsey intended to mount the long 32-pdr. originally planned for the Oneida on her.In the autumn of 1811, Woolsey requested the owners of all American merchant vessels to bring them to Sackett’s Harbour for protection. Once there, they would be laid up for the winter. Then, in case of war, the British, whom Woolsey described as zealous and alert, would be unable to press them into service.71 ·

By early winter of 1811, most of the Oneida’s crew had been recruited in New York City from hardy Atlantic sailors. Sailing by gunboat to Albany, these experienced tars 72 continued their journey overland to Lake Ontario, while a detail of marine recruits accompanied them to

prevent desertion. Once on station, these leathernecks were attached to the gunbrig as a guard.67 Niles’ Weekly Register, July 4, 1812. p.299.

68 Author’s conversation with Col. John Elting.

69 National Archives, Washington D.C. RG-45. Microfilm Series M148. Officer’s Letters received by Secretary

Navy below the rank of commander, 1802-1884. Lieut. Woolsey to Hamilton, July 23, 1811. Nr. 141.

70 A South Carolina Plantation owner usually drunk by noon, Hamilton, an incompetent, had little knowledge of naval affairs. Because of his personal relationship to the president, he held this key position until, Madison reluctantly “accepted” Hamilton’s resignation in December, 1813.

71 National Archives, Washington D.C., RG45, Letters Recieved by the Secretary of the Navy from Officers below the rank of Commander, 1802-1884. Microfilm Series M148. Roll9, Nr. 200, Woolsey to Hamilton, Oct. 18, 1811.

72 Early nickname for sailors.They were without weapons, ammunition or uniforms. To avoid delays their clothing and equipment was shipped directly to Sackett’s Harbour when it became available.73

By April20, 1812, Lake Ontario was free of ice and open for navigation. If the differences between the United States and Great Britain were not amicably settled, Woolsey was determined to have the Oneida prepared for war. Three-hundred cannonballs for the 32-pdr. at Oswego were ordered and shot for the guns was loaded on the merchant vessels. Work began on a blockhouse at Sackett’s Harbour on the bluff overlooking the lake. Woolsey hoped to complete the crew of the Oneida from local militia or at Oswego. Because smuggling activities were spiraling, customs officials urged Woolsey to watch all vessels bound for Cape Vincent for they knew that produce shipped to this small border settlement at the source of the St. Lawrence River was

eventually intended for the illegal Canadian market. By early June, the efficient Woolsey had the

Oneida and her crew prepared for any eventuality.74It was well that Woolsey did, for on June 1, 1812, after repeated efforts to arrive at a diplomatic settlement, President James Madison sent his war message to Congress. The President had a history of demonstrating his willingness to use force to accomplish his nation’s goals

despite his reputation as “Father of the Constitution.”75 In the 1790’s he approved the campaigns

against the Indians in the Northwest and also supported military action against the Barbary Pirates in 1803. He fully backed Jefferson’s Embargo Act of 1807. As Secretary of State, Madison guided foreign policy which led to the Louisiana Purchase, doubling the size of the United States. As commander-in-chief he now charged, “…commerce has been plundered in every sea,” as British cruisers were violating the rights of American waters. Additionally, he blamed the British in Canada for instigating Indian unrest on the frontier .Following his war message, Congress went into secret session for debate. The House of Representatives voted for war along party lines on June 4, 79 to 49. The Senate concurred, with a closer vote, 19 to 13. This was to become in many ways, a partisan Democrat-Republican war, with strong opposition in some sections of the country, especially Federalist New England and Northern New York.

The die cast, Britain’s ambassador was summoned to the State Department and informed that a state of war existed between his country and the United States. The War Hawks had

73 National Archives, Washington D.C., RG45, Microfilm Series M148. Roll9. Officers Letters to the Secretary of the Navy below the rank of commander. Woolsey to Hamilton, Nov. 12, 1811.

74 National Archives, Washington D.C., RG45, Microfilm Series M148, Officers Letters below the rank of

Commander. Sept. 1812- June 1813. Woolsey to Hamilton, June 1812.

75 MADISON, James. (1751-1836). Madison was brought up in Orange County, Virginia, and attended Princeton (then called the College of New Jersey). He was a student of history, government and well-read in law. He participated in the framing of the Virginia Constitution in 1776 and served in the Continental Congress. Madison made a major contribution to the ratification of the Constitution by writing, with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay the Federalist essays. In Congress, he helped frame the Bill of Rights and enact the first revenue legislation.

Madison was elected fourth President in 1808 following Thomas Jefferson and embarked on a course that resulted in war with Great Britain. On June 18, 1812, the United States declared war in which its forces initially took a severe trouncing but over the course of hostilities, resulted in the creation of a professional battle-hardened army and navy. In retirement (1817) at his estate, Montpelier, Madison spoke out against the disruptive states’ rights influences that by the 1830s threatened to shatter the union. He died at Montpelier in 1836.successfully pushed their militarily unprepared nation into conflict with the world’s leading maritime power. They then fixed their eyes northward in anticipation of fulfilling one remaining goal of the American Revolution – conquest of Canada. But, it was necessary for the United States to strike immediately and forcefully if she might conquer Upper Canada before British re inforcements could arrive from across the ocean. The question was, could American arms strike in time?

Pals

GracePeters

@gracepeters

Black Owl

@blackowl

Battle of Sacketts Harbour

@the-battle-of-sacketts-harbor

Bobby

@bobby

XFile

@xfile